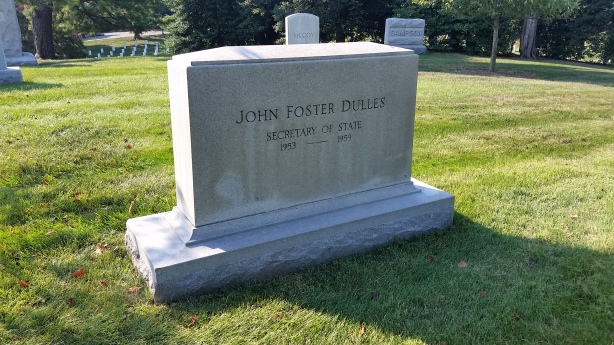

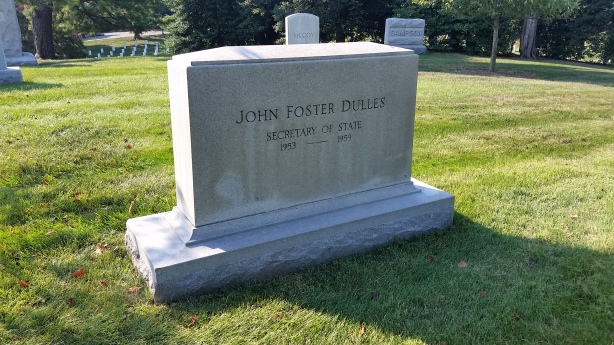

Gravesite of John Foster Dulles

On this afternoon’s bike ride I ventured back over to Virginia to visit one of my favorite places to walk around – Arlington National Cemetery. During this visit I happened to see the name John Foster Dulles on one of the large gravestones that stand out compared to the smaller and uniform sized markers that are most common there. The name stood out to me because one of the two major airports in the D.C. area is Washington Dulles International Airport, and I wondered if it was named after him. Other than that, I knew nothing about John Foster Dulles, nor about the origin of the local airport’s name. So I decided to look further into later when I got home.

It turns out that the airport was, in fact, named after the man whose gravestone I encountered at the cemetery that simply reads, “Secretary of State 1953 – 1959.” (Which I found odd. It did not even include the usual information, such as when he was born or when he died.) So I knew that about him too. But it turns out that there was more to the man than those two things. He was also an American diplomat and politician who was a very important figure in the early years of the Cold War and world history.

Born in D.C. on February 25, 1888, Dulles was one of five children and the eldest son born to Allen Macy Dulles, a Presbyterian minister, and his wife, Edith Foster Dulles. His paternal grandfather, John Welsh Dulles, had been a Presbyterian missionary in India. And his maternal grandfather, John Watson Foster, was the 32nd Secretary of State under President Benjamin Harrison. One of Dulles’s uncles, Robert Lansing, also was later appointed the 42nd Secretary of State during the Woodrow Wilson administration. And Dulles himself eventually became the 52nd Secretary of State. But I’m getting ahead of myself, so let’s go back.

Dulles was raised and went to public schools in Watertown, New York, before attending Princeton University, where he graduated as a member of Phi Beta Kappa in 1908. He then returned here to D.C. to attend the George Washington University Law School. After graduating, he moved to New York City to accept a position at the law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, where he specialized in international law. Dulles became a partner at Sullivan & Cromwell. His younger brother, Allen Welsh Dulles, would later also become a partner at the firm before leaving to become the first civilian director of the Central Intelligence Agency at the same time Dulles became U.S. Secretary of State. But again, I’m getting ahead of myself.

After the outbreak of World War I, Dulles tried to join the United States Army but was rejected because of poor eyesight. Instead, Dulles received an army commission as major on the War Industries Board. During this time Dulles traveled throughout Central America under the guise of work for his former law firm, but he was really working with his Uncle Robert, then Secretary of State, to support anti-German sentiment in the region. Although a Republican, Dulles would later serve under Democrat President Woodrow Wilson as legal consul for the United States’ delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, which resulted in the Treaty of Versailles to officially end World War I. He also helped write the Dawes Plan, which alleviated Germany’s reparations after that war.

During and subsequent to World War II, Dulles helped prepare the United Nations charter at Dumbarton Oaks here in D.C., and in 1945 served as a senior adviser at the San Francisco United Nations conference. When it became apparent that a peace treaty with Japan could not be concluded with the participation of the Soviet Union, President Harry Truman and his secretary of state, Dean Acheson, decided not to call a peace conference to negotiate the treaty. Instead, they assigned to Dulles the difficult task of personally negotiating and concluding the treaty. Dulles traveled to the capitals of many of the nations involved, and by 1951 he succeeded and the previously agreed to treaty was signed in San Francisco by Japan and 48 other nations.

During the course of his career Dulles also served as the foreign policy advisor on Thomas Dewey’s failed 1944 and 1948 presidential campaigns. Subsequently, in 1949, Governor Dewey appointed Dulles to fill the vacancy caused by the illness and resignation of Senator Robert F. Wagner. Dulles served for four months before his defeat in a special election against Herbert H. Lehman.

After Dwight Eisenhower won the 1952 presidential election, he chose Dulles as Secretary of State. Throughout his tenure, Dulles favored a strategy of massive retaliation in response to Soviet aggression and concentrated on building and strengthening Cold War alliances, most prominently the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). He was the architect of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, an anti-Communist defensive alliance between the U.S. and several nations in and near Southeast Asia. He also initiated the Manila Conference in 1954, which resulted in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) pact that united eight nations either located in Southeast Asia or with interests there in a neutral defense pact. This treaty was followed in 1955 by the Baghdad Pact, later renamed the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) Pact, uniting the so-called northern tier countries of the Middle East – Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Pakistan – in a defense organization. He was also instrumental in putting into final form the Austrian State Treaty in 1955, restoring Austria’s pre-1938 frontiers and forbidding a future union between Germany and Austria, as well as the Trieste Agreement, providing for partition of the free territory between Italy and Yugoslavia.

During his time as Secretary of State, Dulles along with his brother Alan, who had been appointed the Director of the CIA, helped instigate the 1953 Iranian coup d’état, which overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, in favor of strengthening the monarchical rule of the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Dulles was also involved in the coup d’état in Guatemala in 1954, along with his former law firm, Sullivan & Cromwell. At the time, the firm represented the United Fruit Company (UFC), which had major holdings in Guatemala. UFC used its lobbying power, through the firm and through other means, to convince President Dwight Eisenhower and Secretary of State Dulles, to depose the democratically elected President of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz.

Around this same time Dulles advocated support of the French in their war against the Viet Minh in Indochina but rejected the Geneva Accords between France and the communists, instead supporting South Vietnam after the Geneva Conference in 1954. This was an early prerequisite for the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, which resulted in The Vietnam War, also known as the Second Indochina War, a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia which lasted from November 1, 1955 to the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, during which time an estimated 47,434 American soldiers were killed.

Three factors determined Dulles’ foreign policy. They were his strong belief, as an international lawyer, in the value of treaties; his powerful personality, which often insisted on leading rather than following public opinion, and; his profound detestation of communism, which was in part based on his deep religious faith – and not necessarily in that order. Of the three, passionate hostility to communism was the leitmotiv of his policy. In fact, wherever he went, he carried with him Joseph Stalin’s book entitled “Problems of Leninism,” and impressed upon his aides the need to study it as a blueprint for conquest similar to Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. So perhaps one of most important aspects of Dulles’s legacy was his point of view on communism and the resultant influence and impact that viewpoint had on foreign policy and the spread of communism.

As far as his personal life, Dulles married Janet Pomeroy Avery, granddaughter of Theodore M. Pomeroy, a former Congressman and Speaker of the House of Representatives, in 1912. They had two sons and a daughter. Their older son John W. F. Dulles was a professor of history and specialist in Brazil at the University of Texas at Austin. Their daughter, Lillias Dulles Hinshaw, became a Presbyterian minister. And their other son, Avery Dulles, converted to Roman Catholicism, entered the Jesuit order, and became the first American theologian to be appointed a Cardinal.

Dulles developed colon cancer in 1956, for which he was operated on after it had caused a bowel perforation. He experienced abdominal pain at the end of 1958 and was again hospitalized, at which time he was diagnosed with diverticulitis. In January of 1959, Dulles returned to work, but with more pain and declining health underwent abdominal surgery in February of that year at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, when the cancer’s recurrence became evident. After recuperating from the surgery in Florida, Dulles returned to D.C. and resumed working while undergoing radiation therapy. With further declining health and evidence of bone metastasis, he resigned from office on April 15, 1959. He died at Walter Reed just six weeks later, on May 24, 1959, at the age of 71. Funeral services were held in Washington National Cathedral on May 27, 1959, and he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, where today I saw his gravestone.