Mamie Johnson got her nickname from a trash-talking third baseman for the Kansas City Monarchs named Hank Bayliss. Although that was not his intention. Standing at the plate opposite the 5-foot-3, 115-pound right-handed pitcher, Bayliss took a hard strike, after which he stepped out of the batter’s box and said, “Why, that little girl’s no bigger than a peanut. I ain’t afraid of her.” But it would take more than trash talking when facing off against her. She proceeded to strike him out. After that, Johnson decided to turn the jab into her nickname. And from then on the first female pitcher to play in the Negro Leagues was affectionately known as “Peanut.”

Peanut was born Mamie Lee Belton in Ridgeway, South Carolina on September 27, 1935, to Della Belton Havelow and Gentry Harrison. In 1944 her family moved, eventually settling down here in D.C. In 1952, when she was still just 17 years old, she and another young woman went to a tryout in nearby Alexandria, Virginia, for the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. This was the same league portrayed in the film “A League of Their Own.” But despite Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball (MLB) five years earlier, the women’s league remained segregated, and she was turned away. Years later she was quoted as saying, “They looked at us like we were crazy. They wouldn’t even let us try out, and that’s the same discrimination that some of the other black ballplayers had before Mr. Robinson broke the barrier. I never really knew what prejudice was until then.”

She would later recall her rejection by the women’s league, however, was a blessing in disguise. Because the later that year a scout saw Johnson dominate a lineup of men while playing for a team sponsored by St. Cyprian’s Catholic Church in D.C. The scout invited her to try out for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues, the same team that launched the career of Hall of Famer Hank Aaron. She would go on to play three seasons with the Clowns, from 1953 through 1955.

At the plate the right-handed batter had a respectable batting average in the range of .262 to .284. But with a career 33–8 win-loss record, she was not as good a batter as she was a pitcher. A right-handed pitcher with a deceptively hard fastball, Peanut also threw a slider, circle changeup, screwball, knuckleball, and curveball, a pitch she received pointers on from Satchel Paige. Of Paige, she said, “Tell you the truth, I didn’t know of his greatness that much. He was just another ballplayer to me at that particular time. Later on, I found out exactly who he was.”

Peanut’s brief professional baseball career ended before her 20th birthday, but in that time she amassed a lifetime of interesting stories about a bygone era of playing baseball in a league born of segregation. After retiring, she earned a nursing degree from North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University and established a 30-year career in the field, working at Sibley Memorial Hospital back here in D.C. She later operated a Negro Leagues memorabilia shop in nearby Capitol Heights, Maryland.

Peanut eventually received recognition for her career in the Negro Leagues. In 1999, she was a guest of The White House. And in 2008, Peanut and other living players from the Negro Leagues ere were drafted by major league franchises prior to the 2008 MLB First year Draft. Peanut was selected by the Washington Nationals. Peanut also spoke at an event entitled Baseball Americana 2009, which was organized by The Library of Congress. And in 2015, a Little League named for her was formed in D.C.

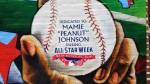

Among these and many other accolades is a mural featuring Peanut, along with Josh Gibson, another prominent Negro League player from D.C. who was also known as the “black Babe Ruth”, and played for the Homestead Grays, who played home games at D.C.’s Griffith Stadium. The mural was created last year here in D.C. It is located in the alley off of U Street (MAP) between Ben’s Chili Bowl and the Lincoln Theater in northwest D.C.’s Shaw neighborhood, and was the destination of this lunchtime bike ride. Today is opening day for MLB and the Washington Nationals. And normally I would ride by Nationals Park on Opening Day. But since I couldn’t go to the game this afternoon, I decided to go see this baseball-themed mural during today’s lunchtime bike ride.

The colorful mural was painted by D.C. artist Aniekan Udofia, and is directly across the alley from his mural featuring the likes of Barack and Michelle Obama, Prince and Muhammad Ali on the side of Ben’s Chili Bowl. The mural was conceived and orchestrated by MLB to kick off the weeklong festivities leading up to last fall’s MLB All-Star Game at Nationals Park. At the unveiling ceremony, a speaker stated that one of the goals of the mural was to “inspire others to learn about Johnson, Gibson and the Negro Leagues.” And today I did just that.

[Click on the photos to view the full-size versions]