The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

One of the most recently dedicated of D.C.’s major national memorials is the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, and that was the destination of this bike ride. The memorial opened to the public three years ago today, on August 22, 2011, after more than two decades of planning, fund-raising and construction. A dedication ceremony for the memorial was originally scheduled for later that same week, and had the ceremony taken place it would have coincided with the 48th anniversary of the “I Have a Dream” speech that King delivered on August 28, 1963, from the steps of The Lincoln Memorial. Unfortunately, the dedication ceremony could not be held because of Hurricane Irene, and was rescheduled for later that fall.

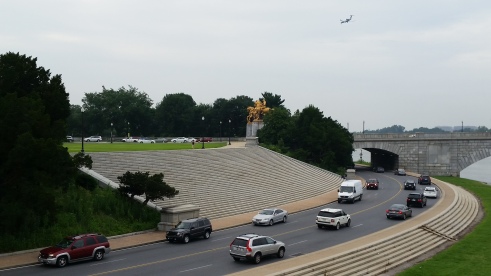

The memorial is located on a four-acre plot of land in southwest D.C.’s West Potomac Park, and is situated on one of the most prestigious sites that was remaining near the National Mall, at the northwest corner of the Tidal Basin near The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial. It is situated on a sightline linking The Lincoln Memorial to the northwest and The Jefferson Memorial to the southeast. The official address of the monument is 1964 Independence Avenue (MAP), an address specifically assigned to symbolically commemorate the year the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law.

The large centerpiece of the multi-faceted memorial is based on a soul-stirring line from King’s “I Have a Dream” speech: “Out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope.” The “Stone of Hope” is a 30-foot statue of a standing King, who is depicted with his arms folded in front of him, gazing over the Tidal Basin toward the horizon. The sculpture was carved from 159 granite blocks that were assembled to appear as one singular piece. The Stone of Hope seems to have emerged from within a large boulder behind it, representing the “Mountain of Despair,” which has been split in half as it gives way to the Stone of Hope.

The memorial also includes a 450-foot crescent-shaped inscription wall, made from granite panels, that is inscribed with 14 excerpts of King’s sermons and public addresses to serve as living testaments of his vision of America. The earliest inscription is from the time of the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, and the latest is taken from his final sermon, delivered in D.C.’s National Cathedral just four days before his assassination in 1968.

Landscape elements of the Memorial include American elm trees, Yoshino cherry trees, liriope plants, English yew, jasmine and sumac. And at the entrance to the Memorial, there are a bookstore and National Park Service ranger station which includes a gift shop, audio visual displays, touch-screen kiosks and more.

Like most other memorials, monuments, statues, and just about everything else in D.C., The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial is not without controversy. In fact, the memorial has been involved in or at the center of a couple of controversies.

One controversy had to do with an inscription found on the Stone of Hope. Each side includes a statement attributed to King. The first reads “Out of the Mountain of Despair, a Stone of Hope,” the quotation that serves as the basis for the monument’s design. The words on the other side of the stone used to read, “I Was a Drum Major for Justice, Peace, and Righteousness.” On first reading, it seems an odd choice considering the phrase “I have a dream” is found nowhere on the monument. The drum major quote, as it was inscribed on the monument, is a paraphrased version of a longer quote by King: “If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.” The memorial’s use of the paraphrased version of the quote was heavily criticized as turning a conditional statement into a boast, which was in direct opposition to the meaning of his sermon about the evils of self-promotion from which the quote is taken. Among the most vocal about this quote was the poet, Maya Angelou, who knew King, and said that the misquote makes King look like an “arrogant twit” and called for it to be changed, at whatever the cost. The inscription was removed in August of last year.

The other controversy has to do with the King family demanding that “The Washington, D.C. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation,” which oversees the memorial, pay licensing fees to use King’s name and likeness. The issue of the fee originally delayed the building of the memorial. The memorial’s foundation, beset by delays and a languid pace of donations, stated at the time that “the last thing it needs is to pay an onerous fee to the King family.” And historian David Garrow, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography of King, said, “One would think any family would be so thrilled to have their forefather celebrated and memorialized in D.C. that it would never dawn on them to ask for a penny.” He added that King would have been “absolutely scandalized by the profiteering behavior of his children.” In response to the criticism, the family pledged that any money derived from the memorial foundation would go back to the King Center’s charitable efforts. Eventually, an agreement was reached in which the foundation has paid various fees to the King family, including a management fee of $71,700 back in 2003. Additionally, in 2009, the Associated Press revealed that the King family had negotiated a $761,160 licensing deal with the foundation for the use of King’s words and image in fundraising materials for the memorial.

However, the controversies do not diminish the importance of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, and it remains a lasting tribute to King’s legacy and serves as a monument to the freedom, opportunity and justice for which he stood.